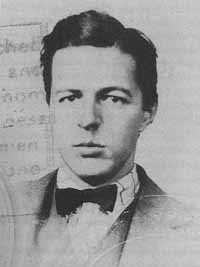

Scofield Thayer was born in a wealthy family, his father, Edward D. Thayer, had made a fortune in the wool trade, so that Thayer never had to engage in business for a living. He was far more interested in the arts. He entered Harward in 1913 and then went on a tour in Europe, accompanied by his tutor. After graduation cum laude in 1913, Thayer attended Magdelen College, Oxford, for further study in classics and philosophy. When the War was declared, he returned to the United States. The Army draft rejected him.

He was therefore at loose ends at the time, so it was a happy coincidence that in the Spring of 1918 in Chicago he finally met Martyn Johnson, who was looking for a congenial backer for The Dial, the old and respectable review which had just been brought to New York from its native Chicago. Thayer was immedidately attracted to the plan, the more so as he deeply admired Randolph Bourne, the brilliant journalist, who was to be one of the editors. Thayer would advance money, not as a loan but considered as a gift. But he also had the project of helping the director to direct the future of the review.

But this was not to be: Randolph Bourne died of pneumonia a few weeks after the Armistice. Then there was a bitter struggle between different members of the staff over politics, and Thayer who did not agree with their stand withdrew. Martyn Johnson's Dial collapsed some months afterwards and Johnson had to sell his Dial Publishing Company stock at the end of 1919. Then it was that Scofield Thayer brought forth a new partner, Dr. Sibley Watson.

To see Dr. Watson and Mr. Scofield Thayer together was something to remember. It would have required a Henry James to tabulate and record each interesting tarot card of this astounding association. (...) How quaint it was to see these two working together for the aesthetic enlightment of the Western world! It was like seeing a proud, self-willed, bull-calf bison, fed on nothing but golden oats, yoked to the plough with a dainty, fetlocked, dapple-grey unicorn, who would, an' he could, step delicately over the traces and scamper to the edge of the prairie, where, under the protective colouring of a grove of pale wattle trees, he might be lost to the view of the world. (Llewelyn Powys,The Verdict of Bridlegoose)

The new owners decided that The Dial would become a monthly, that it would publish fiction and drawings, in addition to critical essays. Thayer hoped to provide for America the journal it most needed, but had no illusions. It was a means of publishing the kind of art and literature he liked, but he did not expect to earn any money out of it. It heralded the Twenties with its first issue, in January 1920.

Thayer took the greatest trouble over the review, and he it was who arranged the text as carefully as he arranged the illustrations. The result is overwhelming: the best work was chosen from the start, traditionalists as well as experimentalists, among writers as among painters and sculptors, from Cézanne and Picasso (constantly shown) to Maillol, Chagall, the School of Paris, Modigliani, Matisse, de Chirico, but also le douanier Rousseau for the arts, from Valéry and Hofmannsthal to Yeats and Proust, including of course, both John Cowper and Llewelyn Powys, for literature. Rimbaud (whose Saison en Enfer was translated by Watson), Joyce, Pound, e.e. cummings or T.S. Eliot among many others had poems published in The Dial. Music was reviewed by the discerning Paul Rosenfeld, who praised Stravinsky, but also Varèse, Copland, Schönberg and de Falla, but was never a major concern for Thayer, as were literature and the arts. However, as a result of Thayer's insistence on excellence, The Dial triumphed and is an extraordinary review, even now. Thayer and Watson were far ahead of their contemporaries and their taste is incomparable.

It was Scofield Thayer who insisted on having Alyse Gregory, one of his closest friends, on his staff in 1923 as Managing Editor, which responsibility she fulfilled, gracefully and efficiently, until her departure for England in 1925, when she was replaced by the poet Marianne Moore.

In 1921 Thayer sailed for Europe and settled in Vienna, which was to be his final residence after 1926. But he continued to take an active part in The Dial and regularly sent instructions to the staff. Unfortunately, Thayer's health started to deteriorate. He suffered from mental breakdowns, which worsened, and he resigned as Editor in June 1926. Towards the close of the decade, a new age was dawning, politically and ideologically very different from the review's aesthetic aims. The Dial ended with the July 1929 issue. It was felt as a great loss and Padraic Colum wrote to Marianne Moore:

I can honestly say that I feel as if a bit was gone out of my own life. Writing for The Dial was not like writing for any other periodical. I know I shall never have again such sympathetic editors. My own loss is a great one, but even if I had not been attached to The Dial through writing for it I should feel at a loss because of the defeat of so gallant an intellectual adventure...

As Nicholas Joost writes in his invaluable Scofield Thayer and The Dial (to which I am much indebted):

Thayer and Watson first gave America a review of the kind that their predecessors had envisioned, a periodical as beautiful as it was intelligent, urbane and cosmopolitan only because it incorporated in its conception the best, according to its directors' lights, that was possible in America.

|