Theatres

From 1912 to 1917 Powys became very interested in theatrical ventures. Thus in November 1913 he writes to his brother Llewelyn:

I am now trying my hand at play-writing. I rather think I may hit the right vein here eventually. I have written one play which has certain faults; and I am off on onother. I think I shall in the end make a success of one or the other. I have been watching their rehearsals at the Little Theatre and I see the kind of thing they want. I have made two beginnings of a story, but neither please me. One is too fantastic and the other too ordinary. I may with your help be able to blend them perhaps. But plays are what interest me just at this moment. If only I could manage anything in that line that would be the best escape from lecturing, because plays pay so well.(Letters to his Brother Llewelyn, 25 Nov. 1913)

He was also a friend of Maurice Browne, whose Little Theatre in Chicago, 'one of the greatest of avant-garde theatre companies... was probably the most important centre for dramatic experiment in the English-speaking world'. (Introduction to Paddock Calls, a play by John Cowper, published in 1984 by Greymitre Books, London)

I've never been more like an inspired Pantaloon, in a setting designed by Aubrey Beardsley, and a Libretto composed by Ernest Dowson, than I was then; and here, while against some background put up by Raymond Jonson I interpreted such writers as Wilde and Verlaine and Heine and Blake and Walter Pater, I danced my dance before dancers, and played my acts before actors.(Autobiography)

But think what an oasis it was in my lecturing life - and with no shred of responsibility either, for poor Maurice had to do all the worrying — when I could sit for hours at their rehearsals in this secluded place, like a centaur drunk with berry-juice in a fairy-ring, looking, and you may believe I did not weary of these vigils, as the lithe and lissom figures of Maurice Browne's young ladies, as they practised the chorus of some unending play, perhaps of Euridipes, perhaps of Yeats, perhaps of Maurice himself. How these devoted young women used to work! And how Maurice Browne, his vivid features convulsed with aesthetic passion, would skip up to the stage in a frenzy of excitement and then rush back again to his seat, where he would sit crouching, sphinx-like and glowering, with an expression like that of Kubla Khan, when, between "sunny dome" and "caves of ice", he heard the "ancestral voices"... (Autobiography)

My Chicago Little Theatre life was indeed one continuous performance of the Actor in me. And what an exciting time it was! Everyone came to Maurice's Pedagogic Province. Floyd Dell brought Dreiser. Dreiser brought Masters, and I lectured upon them all, to them all! Arthur Ficke was always coming up from his "home-town", often bringing Witter Bynner with him, and Llewelyn Jones was constantly there. Maurice must have had a real genius for gathering people about him.

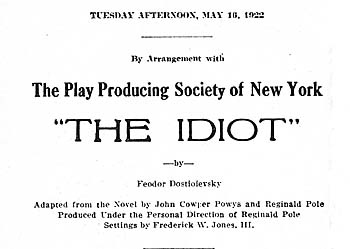

John Cowper wrote several plays himself but Maurice Browne refused them for his Theatre, sometimes against the wish of the other members of his company. With Reginald Pole John Cowper had done an adaptation from Dostoievsky's The Idiot, which was performed at the Republic Theatre, New York, on April 7, 1922. Further performances were given at the Little Theatre, New York, on April 9 and May 16 of the same year. This adaptation has not up to now been published, although it is a remarkable rendering of Dostoievsky's masterpiece.

|

On the spur of that — relative — success, he wrote another play, Paddock Calls, while he was in California, towards the end of 1922 and had great hopes of having that play performed under Browne's direction, at the Plaza at San Francisco.

I have begun another play, tho' they have not yet 'taken' Paddock Calls. But if I make this play — this other play — real literature, it and even Paddock Calls (revised a little) could be printed in a book — eh?

I swear Paddock Calls is as good as any of those Ibsen things — Rosmersholm and Hedda Gabler — and this new one shall be even better still. I will not be careless. I will weigh every word, I will treat it like a poem written to Lulu. I enjoy this play — writing, you know. I think it suits my style very well. But I must not worry about their taking it or not taking it — I must interest myself in it, eh? (Letters to His Brother Llewelyn, 7 November 1922)

Unfortunately, due to some dispute between Jessica Colbert and the patron she had chosen, it did not get a rehearsal and everything was stopped. After the collapse of his theatrical expectations, John Cowper never came back to writing plays again or even to going to see one. But nevertheless he still kept enough interest to get interested in a play, The Dybbuk, 'a Jewish Antigone', which was performed by the Habima company in 1927.

And one felt that this totality, this astral body of weird beauty, was so saturated with Hebrew tradition that every part and parcel of it, every curve, every contour, every note, every light and shadow, was flesh of Hebrew flesh. Never since the old Greek drama has anything appeared so autochtonous, so woven — like that Jewish garment once diced for by Roman soldiers — 'without a seam'.

But where The Dybbuk is so especially 'human' is that it releases the ironic malice of our mind as well as its spiritual passion. The ballonim's songs equally with the beggars' dance are a sardonic hit-back that relaxes with an unspeakable relaxation a certain pent-up stoicism of assent upon which the order of life, its formality and its decency, has inevitably insisted. This is that metaphysical relaxation which all great farce aims at; and the Jewish genius for just this has been displayed, ere now, not only in Heine's mockeries, but in the traditional 'comic Jew' of the modern American burlesque show! (Menorah Journal, Aug. 1927, in Elusive America, Paul Roberts ed., Cecil Woolf, London, 1994)

Towards the end of his life, Dreiser also had an occasion to see The Dybbuk. As Margaret Tjader says in her Theodore Dreiser, A New Dimension (1965), "Dreiser, who had always believed in the supernatural world even in his worst days of scoffing at religion, was deeply shaken by this drama, as we all were. It was a strange thing that he should see this play at this time, a terrible and beautiful thing, for psychic phenomena had always seemed real to him as when he had gone to séances, and played with Ouidja boards, or glimpsed the strange, horrible faces he said he saw sometimes around his bed at night."

The Dybbuk was made into a film by Michal Waszynski in 1937. It was the very last of the yiddish masterpieces to be produced before the war.

|